It’s an inescapable fact that genre fiction is littered with tropes. Tropes provide something of a backbone to almost any story you will ever read, particularly in science fiction and fantasy. They are the thing we writers use to ground our stories before drenching them in weird locals and unfathomable magic. From the enemies-to-lovers sensation that is Fourth Wing to the chosen one heart of pretty much every young adult fantasy book, we can find them all over contemporary fantasy. But nowhere is that truer than with found family.

It can take many forms. From the at times uncomfortable intimacy of an AI implant in J.S. Dewes’s Rubicon to the “we’re all going to stab each other eventually” bloodlust of M.J. Kuhn’s Among Thieves. The question is, why? What is it about found family that keeps us coming back to it? Does its ubiquity make it tired? Or is its universality speaking to something essential in the human psyche?

Even a brief trek through the annals of storytelling history makes me think it’s likely the latter. Take the platonic friendship between Enkidu and Gilgamesh in the eponymous Epic of Gilgamesh. It shows that even four thousand years ago we humans believed in the power of friendship to change us in fundamental ways.

And what is Arthur and his round table but a bunch of bros finding solace in friends who understood them better than anyone else. (Gym, tan, grail quest, anyone?) Even Snow White manages to turn a single girl’s unconventional living situation into an ode to found family. Those seven dwarves don’t just give her a home, they set out to kill her murderous stepmother too. (Which as we all know is the sign of a true friendship.)

And what would a discussion about found family be without mentioning The Lord of the Rings, that grave upon which nearly all modern western fantasy was built? The trilogy would be unrecognizable were it not for the friendships forged in Fellowship. And don’t forget, it was Sam’s love for Frodo that truly saved Middle-earth.

This tiny slice of storytelling history proves that found family tales are nothing new, but why? What is it that draws us to them year after year? I think that answer is a slippery one, because the reasoning doesn’t remain fixed over time. It is intensely personal to each reader, including me.

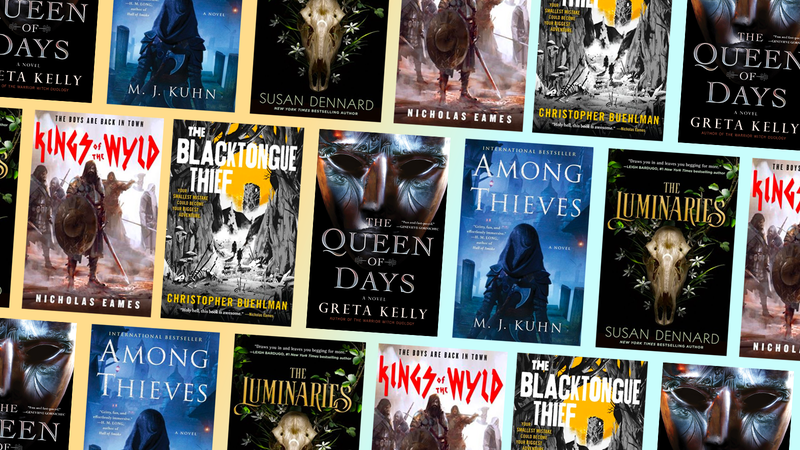

In my youth I remember being drawn to found family stories like the proverbial moth to flame, and I know I wasn’t alone. For so many of us, the friendships we forged in middle and high school were formative. When you’re little more than an open nerve of hormones, sure that no adult has ever been where you are now, finding a place in stories and in families different than your own can be a lifeline. It makes sense to turn to fiction when your real family seems to willfully misunderstand you. Books like The Luminaries, One For All, and Together We Burn can make you feel seen in a way that nothing else can.

But life changes, as it always does, and suddenly you’re in your twenties. For many of us, myself included, it was the first time we were on our own and found family tales took on a different meaning. A different importance. It wasn’t simply about finding people who understood you because your parents didn’t, and more because of feeling adrift, searching for a sense of home in foreign lands. The hunt was elusive and rare and terribly precious. It was this, as well as the revelation that college-aged people read too that made books like Ninth House and The Atlas Six and Divine Rivals feel less like losing yourself and more like coming home.

After college, those reasons turned over once more. With careers and marriages pulling everyone in different directions, I suddenly found myself faced with the seemingly impossible prospect of forming adult friendships… I mean, what do you even talk to a person about when you don’t have the shared context of a horrid econ professor?

Nothing really prepares you for the reality of adulthood, the feeling of coming in late to a party wearing clothes that don’t quite fit. Just when you think you’ve left the dreaded high school lunchroom behind you find yourself invited to the neighborhood Facebook group. And once again, found family stories became a refuge. From Kings of the Wyld to The Blacktongue Thief and The Hexologists, I found safe havens in the flawed and tangled relationships of others, and the hope that friends can exist alongside family too.

I don’t know what the trope will mean to me in the future, or how its meaning will change with the passage of time. But right now? Writing this with a pair of chaos gremlins—I mean toddlers—chasing imaginary dragons in the backyard, my reason for loving this well-worn trope has changed again. It’s a reason that is as simple as it is timeless:

We raise our children like ships, always knowing that one day they will sail away from us, vanishing into the unknown. We know the trials and tribulations that lay ahead, the dangers and joys that lurk in that vast ocean of life. And no matter how much we want to, it isn’t a journey we can join them on. All we can do is watch, and wait, and hope that they will one day return.

And pray that they won’t have to sail those waters alone.

Greta Kelly’s standalone fantasy novel, Queen of Days, is on sale now.

Want more io9 news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about the future of Doctor Who.

Comments

Post a Comment